Arabic alphabet

| Arabic abjad | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Abjad |

| Spoken languages | Arabic |

| Time period | 400 CE to the present |

| Parent systems |

Proto-Sinaitic

|

| Unicode range |

U+0600 to U+06FF |

| ISO 15924 | Arab (#160) |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. | |

| Arabic alphabet | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ا ب ت ث ج ح | |||||

| خ د ذ ر ز س | |||||

| ش ص ض ط ظ ع | |||||

| غ ف ق ك ل | |||||

| م ن ه و ي | |||||

| History · Transliteration Diacritics · Hamza ء Numerals · Numeration |

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

The Arabic alphabet (Arabic: أبجدية عربية ’abjadiyyah ‘arabiyyah) or Arabic abjad is the script used for writing several languages of Asia and Africa, such as Arabic and Urdu. After the Latin alphabet, it is the second-most widely used alphabet around the world.[1]

The alphabet was first used to write texts in Arabic, most notably the Qurʼan, the holy book of Islam. With the spread of Islam, it came to be used to write many languages of many language families including, at various times, Persian, Urdu, Pashto, Baloch, Malay; Fulfulde-Pular, Hausa, and Mandinka (all in West Africa); Swahili (in East Africa); Brahui (in Pakistan); Kashmiri, Sindhi, Balti, and Panjabi (in Pakistan); Arwi (in Sri Lanka and Southern India), Chinese, Uyghur (in China and Central Asia); Kazakh, Uzbek and Kyrgyz (all in Central Asia); Azerbaijani (in Iran), Kurdish (in Iraq and Iran), Belarusian (amongst Belarusian Tatars), Ottoman Turkish, Serbocroat (in Bosnia), and Spanish (in Western Europe). To accommodate the needs of these other languages, new letters and other symbols were added to the original alphabet. This process is known as the Ajami transcription system, which is different from the original Arabic alphabet.

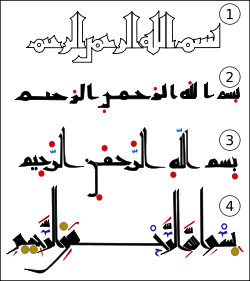

The Arabic script is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 basic letters. Because some of the vowels are indicated with optional symbols, it can be classified as an abjad. Just as different handwriting styles and typefaces exist in the Roman alphabet, the Arabic script has a number of different styles of calligraphy, including Naskh خط النسخ, Nastaʿlīq, Ruq'ah خط الرقعة, Thuluth خط الثُلث, Kufic الخط الكوفي, Sini and Hijazi.

Contents |

Consonants

Collation

There are two main collating sequences for the Arabic alphabet:

- The original abjadī order (أبجدي), used for numbering, derives from the order of the Phoenician alphabet, and is therefore similar to the order of other Phoenician-derived alphabets, such as the Hebrew alphabet.

- The hijāʼī (هجائي) or alphabaʼi order shown in the table below, used where lists of names and words are sorted, as in phonebooks, classroom lists, and dictionaries, groups letters by similarity of shape.

Different collating orders were widely used in the Maghreb until recently, when they were replaced by the Mashreki order. (See Abjad numerals).

Primary letters

The Arabic alphabet has 28 basic letters. Adaptations of the Arabic script for other languages, such as Persian, Ottoman, Urdu, Malay or Pashto, have additional letters, on which see below. There are no distinct upper and lower case letter forms.

Many letters look similar but are distinguished from one another by dots (iʿjam) above or below their central part, called rasm. These dots are an integral part of a letter, since they distinguish between letters that represent different sounds. For example, the Arabic letters transliterated as b and t have the same basic shape, but b has one dot below, ب, and t has two dots above, ت.

Both printed and written Arabic are cursive, with most of the letters within a word directly connected to the adjacent letters. Unlike cursive writing based on the Latin alphabet, the standard Arabic style is to have a substantially different shape depending on whether it will be connecting with a preceding and/or a succeeding letter, thus all primary letters have conditional forms for their glyphs, depending on whether they are at the beginning, middle or end of a word, so they may exhibit four distinct forms (initial, medial, final or isolated). However, six letters have only isolated or final form, and so force the following letter (if any) to take an initial or isolated form, as if there were a word break.

Some letters look almost the same in all four forms, while others show considerable variation. Generally, the initial and middle forms look similar except that in some letters the middle form starts with a short horizontal line on the right to ensure that it will connect with its preceding letter. The final and isolated forms, are also similar in appearance but the final form will also have a horizontal stroke on the right and, for some letters, a loop or longer line on the left with which to finish the word with a subtle ornamental flourish. In addition, some letter combinations are written as ligatures (special shapes), including lām-ʼalif.[2]

For compatibility with previous standards, all these forms can be encoded separately in Unicode; however, they can also be inferred from their joining context, using the same encoding. The following table shows this common encoding, in addition to the compatibility encodings for their normally contextual forms (Arabic texts should be encoded today using only the common encoding, but the rendering must then infer the joining types to determine the correct glyph forms, with or without ligation).

The transliteration given is the widespread DIN 31635 standard, with some common alternatives. See the article Romanization of Arabic for details and various other transliteration schemes.

Regarding pronunciation, the phonetic values given are those of the pronunciation of literary Arabic, the standard which is taught in universities. In practice, pronunciation may vary considerably between the different varieties of Arabic. For more details concerning the pronunciation of Arabic, consult the article Arabic phonology.

The names of the Arabic letters can be thought of as abstractions of an older version where they were meaningful words in the Proto-Semitic language.

Six letters (أ,د,ذ,ر,ز,و) are not connected to the letter following them, therefore their initial form matches the isolated and their medial form matches the final.

| Isolated | Contextual forms | Name | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End | Middle | Beginning | ||||

| ا | ـا | ـا | ا | ʾalif | ʾ / ā | various, including /aː/ |

| ب | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | bāʾ | b | /b/, also /p/ in some loanwords |

| ت | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | tāʾ | t | /t/ |

| ث | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ṯāʾ | ṯ | /θ/ |

| ج | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ǧīm | ǧ (also j) | [ dʒ~ʒ~ɡ ] |

| ح | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ḥāʾ | ḥ | /ħ/ |

| خ | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | ḫāʾ | ḫ (also kh, x) | [ x~χ ] |

| د | ـد | ـد | د | dāl | d | /d/ |

| ذ | ـذ | ـذ | ذ | ḏāl | ḏ (also dh, ð) | /ð/ |

| ر | ـر | ـر | ر | rāʾ | r | /r/ |

| ز | ـز | ـز | ز | zāy | z | /z/ |

| س | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | sīn | s | /s/ |

| ش | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | šīn | š (also sh) | /ʃ/ |

| ص | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ṣād | ṣ | /sˁ/ |

| ض | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ḍād | ḍ | /dˁ/ |

| ط | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ṭāʾ | ṭ | /tˁ/ |

| ظ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ẓāʾ | ẓ | [ ðˁ~zˁ ] |

| ع | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ʿayn | ʿ | /ʕ/ |

| غ | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | ghain | ġ (also gh) | /ɣ/ (/ɡ/ in many loanwords, <ج> is normally used in Egypt) |

| ف | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | fāʾ | f | /f/, also /v/ in some loanwords |

| ق | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | qāf | q | /q/ |

| ك | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | kāf | k | /k/ |

| ل | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | lām | l | /l/, (/lˁ/ in Allah only) |

| م | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | mīm | m | /m/ |

| ن | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | nūn | n | /n/ |

| ه | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | hāʾ | h | /h/ |

| و | ـو | ـو | و | wāw | w / ū / aw | /w/ / /uː/ / /au/, sometimes /u/, /o/ and /oː/ in loanwords |

| ي | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | yāʾ | y / ī / ay | /j/ / /iː/ / /ai/, sometimes /i/, /e/ and /eː/ in loanwords |

Further notes

- The letter ʾalif originated in the Phoenician alphabet as a consonant-sign indicating the glottal stop [ʔ]. Today it has lost its function as a consonant, and, together with yaʾ and wāw, is a mater lectionis, a consonant sign standing in for a long vowel (see below), or as support for certain diacritics (madda and hamza).

- Arabic currently uses a diacritic sign, ﺀ, called hamza, to denote the glottal stop, written alone or with a carrier:

- alone: ء ;

- with a carrier: إ, أ (above or under a ʾalif), ؤ (above a wāw), ئ (above a dotless yāʾ or yāʾ hamza).

- Letters lacking an initial or medial version are never linked to the letter that follows, even within a word. The hamza has a single form, since it is never linked to a preceding or following letter. However, it is sometimes combined with a wāw, yāʾ, or ʾalif, and in that case the carrier behaves like an ordinary wāw, yāʾ, or ʾalif.

In academic work, the glottal stop [ʔ] is transliterated with the right half ring sign (ʾ), while the left half ring sign (ʿ) represents a different letter, with a different pronunciation, called ʿayin.

Modified letters

The following are not individual letters, but rather different contextual variants of some of the Arabic letters.

| Conditional forms | Name | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial | |||

| آ | ـآ | ـآ | آ | ʾalif madda | ʾā | /ʔaː/ |

| ة | ـة | | | tāʾ marbūṭa | h or t / h / ẗ |

/a/, /at/ |

| ى | ـى | | | ʾalif maqṣūra | ā / ỳ | /aː/ |

Ligatures

Unicode primary range for basic Arabic language alphabet is the U+06xx range. Other ranges are for compatibility to older standards and do contain some ligatures. The only compulsory ligature for fonts and text processing in the basic Arabic language alphabet range U+06xx are ones for lām + ʼalif. All other ligatures (yāʼ + mīm, etc.) are optional. Example to illustrate it is below. The exact outcome may depend on your browser and font configuration.

- (initial or isolated) lām + ʼalif (lā /laː/):

-

- لا

Note: Unicode also has in its Presentation Form B FExx range a code for this ligature. If your browser and font are configured right for Arabic, the ligature displayed above should be identical to this one, U+FEFB ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF ISOLATED FORM:

-

- ﻻ

- (final or medial) lām + ʼalif (lā /laː/):

-

- ـلا

Note: Unicode also has in its Presentation Form B U+FExx range a code for this ligature. If your browser and font are configured right for Arabic, the ligature displayed above should be identical to this one, U+FEFC ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF FINAL FORM:

-

- ـﻼ

Another interesting ligature in the Unicode Presentation Form A range U+FB50 to U+FDxx is the special code for glyph for the ligature Allāh (“God”), U+FDF2 ARABIC LIGATURE ALLAH ISOLATED FORM:

-

- ﷲ

This latter ligature code again is a work-around for the shortcomings of most text processors, which are incapable of displaying the correct vowel marks for the word Allāh, because it should compose a small ʼalif sign above a gemination šadda sign. Compare the display above to the composed equivalents below (the exact outcome will depend on your browser and font configuration):

- lām, (geminated) lām (with implied short a vowel, reversed) hāʼ :

-

- لله

- ʼalif, lām, (geminated) lām (with implied short a vowel, reversed) hāʼ :

-

- الله

Gemination

Gemination is the doubling of a consonant. Instead of writing the letter twice, as in English, Arabic places a W-shaped sign called šadda, or shadda, above it. (The generic term for such diacritical signs is harakat). When a shadda is used on a consonant which also takes a kasra (a dash below the consonant indicating that it takes a short /i/ as its vowel), the kasra may be written between the consonant and the šadda rather than in its normal place.

| General Unicode |

Name | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| 0651 ّ ّ |

šadda | (consonant doubled) |

Nunation

| Symbol | ـٌ |

ـٍ |

ـً |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | -un |

-in |

-an |

Nunation (the Arabic term is تنوين, tanwīn) is the addition of a final -n to a noun or adjective. The vowel before it indicates grammatical case. In written Arabic nunation is indicated by doubling the vowel diacritic at the end of the word. There are three of these vowel diacritics, and the signs indicate, from left to right, the endings -un (nominative case), -an (accusative), and -in (genitive). The sign ـً is most commonly written in combination with ا ʼalif (ـًا), ةً (tāʼ marbūṭa تاء مربوطة ) or stand-alone ءً (hamza همزة). An alif should always be written unless the word ends in tāʼ marbūṭa, hamza or is a diptote, even though the -un, -an, or -in is not written. Nunation is used only in formal Arabic (including Modern Standard Arabic); it is absent in everyday spoken Arabic, and many Arabic textbooks introduce even standard Arabic without these endings.

Vowels

In everyday life, when writing Arabic, Long vowels are usually written, but short ones are usually omitted, so the reader must be familiar with the language to understand the missing vowels. However, in the education system and particularly in Arabic Grammar classes these vowels are used since they are crucial to the grammar. An Arabic sentence can have a completely different meaning by a subtle change of the vowels. This is why in an important text such as the Qur'an the vowels are mandated.

Short vowels

Vowels are indicated by diacritical marks placed above or below the letters. In the Arabic handwriting of everyday use, in general publications, and on street signs, short vowels are typically not written. On the other hand, copies of the Qurʼan cannot be endorsed by the religious institutes that review them unless the diacritics are included. It is also generally preferred and customary that they be included whenever the Qurʼan is cited in print. Children's books, elementary-school texts, and Arabic-language grammars in general will include diacritics to some degree. These are known as "vocalized" texts.

Written Arabic cannot be considered truly complete without the notation of its short vowels, which are essential to it. They convey information not coded in any other way. Like dotted letters, diacritical marks were a later addition to the writing system.

Short vowels can be included in cases where word ambiguity could not easily be resolved from context alone, or simply wherever they might be considered aesthetically pleasing.

Short vowels may be written with diacritics placed above or below the consonant that precedes them in the syllable, called harakat. All Arabic vowels, long and short, follow a consonant; in Arabic, words like "Ali" or "alif", for example, start with a consonant: ʻAliyy, ʼalif.

| Short vowels (fully vocalised text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 064E َ◌ |

fatḥa | a | /a/ |

| 064F ُ◌ |

ḍamma | u | /u/ |

| 0650 ِ◌ |

kasra | i | /i/ |

Long vowels

A long a following a consonant other than a hamza is written with a short a sign on the consonant plus an ʾalif after it; long i is written as a sign for short i plus a yāʾ; and long u as a sign for short u plus a wāw. Briefly, aʾ = ā, iy = ī and uw = ū. Long a following a hamza may be represented by an ʾalif madda or by a free hamza followed by an ʾalif.

In the table below, vowels will be placed above or below a dotted circle replacing a primary consonant letter or a šadda sign. For clarity in the table below, the primary letter on the left used to mark these long vowels are shown only in their isolated form. Please note that most consonants do connect to the left with ʾalif, wāw and yāʾ written then with their medial or final form. Additionally, the letter yāʾ in the last row may connect to the letter on its left, and then will use a medial or initial form. Use the table of primary letters to look at their actual glyph and joining types.

| Long vowels (fully vocalised text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 064E 0627 َا◌ |

fatḥa ʾalif (ـَا) | ā | /aː/ |

| 064E 0649 َى◌ |

fatḥa ʾalif maqṣūra (ـَى) | ā / aỳ | /a/ |

| 064F 0648 ُو◌ |

ḍamma wāw | ū / uw (ـُو) | /uː/ |

| 0650 064A ِي◌ |

kasra yāʾ | ī / iy (ـِي) | /iː/ |

In unvocalized text (one in which the short vowels are not marked), the long vowels are represented by the vowel in question: ʾalif, ʾalif maqṣūra (or yeh), wāw, or yāʾ. Long vowels written in the middle of a word of unvocalised text are treated like consonants with a sukūn (see below) in a text that has full diacritics. Here also, the table shows long vowel letters only in isolated form for clarity.

Combinations وا and يا are always pronounced wā and yā respectively, the exception is when وا is the verb ending, where ʾalif is silent, resulting in ū.

| Long vowels (unvocalised text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0627 ا |

(implied fatḥa) ʾalif | ā | /aː/ |

| 0649 ى |

(implied fatḥa) ʾalif maqṣūra | ā / aỳ | /a/ |

| 0648 و |

(implied ḍamma) wāw | ū / uw | /uː/ |

| 064A ي |

(implied kasra) yāʾ | ī / iy | /iː/ |

Diphthongs

The diphthongs [ai] and [au] are represented in vocalised text as follows:

| Diphthongs (fully vocalised text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 064E 064A َي◌ |

fatḥa yāʾ | ay | /ai/ |

| 064E 0648 َو◌ |

fatḥa wāw | aw | /au/ |

Vowel omission

An Arabic syllable can be open (ending with a vowel) or closed (ending with a consonant).

- open: CV [consonant-vowel] (long or short vowel)

- closed: CVC (short vowel only)

When the syllable is closed, we can indicate that the consonant that closes it does not carry a vowel by marking it with a diacritic called sukūn ( ْ ) to remove any ambiguity, especially when the text is not vocalized. A normal text is composed only of series of consonants; thus, the word qalb, "heart", is written qlb. The sukūn indicates where not to place a vowel: qlb could, in effect, be read qalab (meaning "he turned around"), but written with a sukūn over the l and the b (قلْبْ), it can only have the form qVlb. This is one step down from full vocalization, where the vowel a would also be indicated by a fatḥa: قَلْبْ.

The Qur’an is traditionally written in full vocalization. Outside of the Qur’an, putting a sukūn above a yāʼ (representing [iː]), or above a wāw (representing [uː]) is extremely rare, to the point that yāʼ with sukūn will be unambiguously read as the diphthong [ai], and wāw with sukūn will be read [au]. For example, the letters m-w-s-y-q-ā (موسيقى with an ʼalif maqṣūra at the end of the word) will be read most naturally as the word mūsīqā ("music"). If one were to write a sukūn above the wāw, the yāʼ and the ʼalif, one would get موْسيْقىْ, which would be read as *mawsaykāy (note however that the final ʼalif maqṣūra, because it is an ʼalif, never takes a sukūn). The word, entirely vocalized, would be written as مُوسِيقَى. The Quranic spelling would have no sukūn sign above the final ʼalif maqṣūra, but instead a miniature ʼalif above the preceding qaf consonant, which is a valid Unicode character but most Arabic computer fonts cannot in fact display this miniature ʼalif as of 2006.

No sukūn is placed on word-final consonants, even if no vowel is pronounced, because fully vocalised texts are always written as if the ʼiʻrāb vowels were in fact pronounced. For example, ʼAḥmad zawǧ šarr, meaning “Ahmed is a bad husband”, for the purposes of Arabic grammar and orthography, is treated as if still pronounced with full ʼiʻrāb, i.e. ʼAḥmadu zawǧun šarrun with the complete desinences.

| General Unicode |

Name | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0652 ْ◌ |

sukūn | (no vowel with this consonant letter or diphthong with this long vowel letter) |

Ø |

| 0670 ٰ◌ |

ʾalif above | ā | /aː/ |

The sukūn is also used for transliterating words into the Arabic script. The Persian word ماسک (mâsk, from the English word "mask"), for example, might be written with a sukūn above the ﺱ to signify that there is no vowel sound between that letter and the ک.

Additional letters

Additional modified letters, used in non-Arabic languages, or in Arabic for transliterating foreign words only, include:

Sometimes used for writing foreign words

- ڤ — Vāʾ, sometimes used to represent the sound [v] when transliterating foreign words in Arabic. Also used in writing dialects with that sound.[3] Normally the letter ف — fāʾ — is used to transliterate [v]. Also used as pāʾ in the Jawi script. In Tunisia a character similar to vāʾ in its initial and medial forms is sometimes used to represent the phoneme [ɡ]. In final and isolate form it has the form ڨ

which resembles the letter qāf whence it is derived. The sound [v] in Tunisia is rendered using the Arabic letter fāʾ with three dots underneath ڥ.

which resembles the letter qāf whence it is derived. The sound [v] in Tunisia is rendered using the Arabic letter fāʾ with three dots underneath ڥ.

- Also used in Kurdish.

- پ — Pāʾ, used to represent the sound [p] in Persian, Urdu, and Kurdish; sometimes used to represent the letter [p] when transliterating foreign words in Arabic, although Arabic nearly always substitutes [b] for [p] in the transliteration of foreign terms. Normally the letter ب — bāʾ — is used to transliterate [p]. So, "7up" can be transcribed as سفن أب or سڤن أﭖ.

- چ — Čāʾ/chāʾ, used to represent [tʃ] ("ch"). It is used in Persian, Urdu, and Kurdish and sometimes used when transliterating foreign words in Arabic. Nevertheless, Arabic usually substitutes other letters in the transliteration of foreign terms: normally the combination تش — tāʾ and šīn — is used to transliterate the [tʃ] sound, as in "Chad". In Egypt چ is used for [ʒ] (or /dʒ/, which is reduced to [ʒ]).

- Ca in the Jawi script.

- گ — Gāf, used to represent the [ɡ] sound (as in "get"). Normally used in Persian, Kurdish, and Urdu. Often foreign words with [ɡ] are transliterated in Arabic with ك (kāf), غ (ġayn) or ج (ǧīm), which may or may not change the original sound. In Egypt ج is normally pronounced [ɡ].

- ژ — Že/zhe, used to represent the voiced postalveolar fricative [ʒ] in, Persian, Kurdish, Urdu and Uyghur. This is used to transliterate words of foreign origin, mostly French, in Levantine and Maghrebi Arabic dialects. Also, very seldom in Arabic to render [ʒ] sound, and normally, the letter ﺵ (šīn) is used to transliterate [ʒ].

- In addition, when transliterating Spanish or Italian, Arabs write out most or all the vowels as long (a with alif, e and i with ya, and o and u with waw), meaning it approaches a true alphabet.

Used in languages other than Arabic, or in dialects of Arabic

- ڭ - Ng, used to represent the "ng" phoneme in Ottoman Turkish, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Uyghur

- ݙ - used in Siraiki to represent a voiced retroflex implosive

- ݐ - used to represent the equivalent of the Latin letter Ƴ in some African languages such as Fulfulde; not used in Arabic

- ݫ - used in Ormuri to represent a voiced alveolo-palatal fricative, as well as in Torwali

- ݭ - used in Kalami to represent a voiceless retroflex fricative, and in Ormuri to represent a voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative

- ݜ - used in Shina to represent a voiceless retroflex fricative

- ݪ - used in Marwari to represent a retroflex lateral flap, and in Kalami to represent a voiceless lateral fricative

- ﭞ - Ṭhē, represents the aspirated voiceless retroflex plosive in Sindhi

- ﮎ - Khē, represents K in Sindhi

- ﭦ - Ṭe, used to represent Ṭ (a voiceless retroflex plosive) in Urdu

- ڳ - represents a variety of G in Sindhi

- ڱ - represents the "ng" phoneme in Sindhi

- ڻ - represents the retroflex nasal phoneme in Sindhi

- ڀ - represents an aspirated "b" ("bh") in Sindhi

- ژ - Zhe, represents a voiced postalveolar fricative in Persian, Urdu, Kurdish, and Uyghur. Also, very seldom in Arabic to render /ʒ/ sound.

- ڑ - Aṛ, represents a retroflex flap in Urdu

- ڕ - used in Kurdish to represent rr

- گ - Gaf, represents G in Iraqi Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Kurdish, Uyghur, and Ottoman Turkish

- ݣ - Gaf, represents G in informal Moroccan Arabic, as well as officially to transliterate the letter G in many city names such as Agadir (أݣادير), and family names such as El Guerrouj (الݣروج).

- ݢ or ڬ - Gaf, represents G in the Jawi script of Malay

- ے - Bari ye, represents "ai" or "e" in Urdu and Punjabi

- ۆ - represents O (o) in Kurdish, and in Uyghur it represents the sound similar to the French eu and œu (Ø) sound

- ڽ - Nya in the Jawi script

- ڠ - Nga in the Jawi script

- ۏ - Va in the Jawi script

- ڈ - Ḍ in Urdu

Numerals

There are two kinds of numerals used in Arabic writing; standard numerals (predominant in the Arab World), and Eastern Arabic numerals (used in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India). In Arabic, the former are referred to as "Indian numbers" (arqām hindiyyah, أرقام هندية). Arabic (or Hindu-Arabic) numerals are also used in Europe and the rest of the Western World in a third variant, the Western Arabic numerals, even though the Arabic alphabet is not. In most of present-day North Africa, the usual western numerals are used; in medieval times, a slightly different set was used, from which Western Arabic numerals derive, via Italy. Like Arabic alphabetic characters, Arabic numerals are written from right to left, though the units are always right-most, and the highest value left-most, just as with Western "Arabic numerals". Telephone numbers are read from left to right.

| Western (Maghreb, Europe) |

Central (Mideast) |

Eastern/Indian (Persian, Urdu) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | ٠ | ۰ |

| 1 | ١ | ۱ |

| 2 | ٢ | ۲ |

| 3 | ٣ | ۳ |

| 4 | ٤ | ۴ |

| 5 | ٥ | ۵ |

| 6 | ٦ | ۶ |

| 7 | ٧ | ۷ |

| 8 | ٨ | ۸ |

| 9 | ٩ | ۹ |

In addition, the Arabic alphabet can be used to represent numbers (Abjad numerals). This usage is based on the abjadī of the alphabet. أ ʼalif is 1, ب bāʼ is 2, ج ǧīm is 3, and so on until ي yāʼ = 10, ك kāf = 20, ل lām = 30, …, ر rāʼ = 200, …, غ ġayn = 1000. This is sometimes used to produce chronograms.

History

The Arabic alphabet can be traced back to the Nabataean alphabet used to write the Nabataean dialect of Aramaic. The first known text in the Arabic alphabet is a late fourth-century inscription from Jabal Ramm (50 km east of Aqaba), but the first dated one is a trilingual inscription at Zebed in Syria from 512. However, the epigraphic record is extremely sparse, with only five certainly pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions surviving, though some others may be pre-Islamic. Later, dots were added above and below the letters to differentiate them. (The Aramaic language had fewer phonemes than the Arabic, and some originally distinct Aramaic letters had become indistinguishable in shape, so that in the early writings 15 distinct letter-shapes had to do duty for 28 sounds; cf. the similarly ambiguous Pahlavi alphabet.) The first surviving document that definitely uses these dots is also the first surviving Arabic papyrus (PERF 558), dated April 643, although they did not become obligatory until much later. Important texts like the Qur’an were frequently memorized; this practice, which is still widespread among many Muslim communities today, probably arose partially from a desire to avoid the great ambiguity of the script. (see Arabic Unicode)

Later still, vowel marks and the hamza were introduced, beginning some time in the latter half of the seventh century, preceding the first invention of Syriac and Hebrew vocalization. Initially, this was done by a system of red dots, said to have been commissioned by an Umayyad governor of Iraq, Hajjaj ibn Yusuf: a dot above = a, a dot below = i, a dot on the line = u, and doubled dots indicated nunation. However, this was cumbersome and easily confusable with the letter-distinguishing dots, so about 100 years later, the modern system was adopted. The system was finalized around 786 by al-Farahidi.

Arabic printing presses

Although Napoleon Bonaparte generally is given the credit with introducing the printing press to Egypt, upon invading it in 1798, and he did indeed bring printing presses and Arabic script presses, to print the French occupation's official newspaper Al-Tanbiyyah (The Courier), the process was started several centuries earlier.

Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in 1450 was followed up by Gregorio de Gregorii, a Venetian, who in 1514 published an entire prayer book in Arabic script entitled Kitab Salat al-Sawa'i intended for the eastern Christian communities. The script was said to be crude and almost unreadable.

Famed type designer Robert Granjon working for Cardinal Ferdinando de Medici succeeded in designing elegant Arabic typefaces and the Medici press published many Christian prayer and scholarly Arabic texts in the late sixteenth century.

The first Arabic books published using movable type in the Middle East were by the Maronite monks at the Maar Quzhayy Monastery in Mount Lebanon. They transliterated the Arabic language using Syriac script. It took a fellow goldsmith like Gutenberg to design and implement the first true Arabic script movable type printing press in the Middle East. The Greek Orthodox monk Abd Allah Zakhir set up an Arabic language printing press using movable type at the monastery of Saint John at the town of Dhour El Shuwayr in Mount Lebanon, the first homemade press in Lebanon using true Arabic script. He personally cut the type molds and did the founding of the elegant typeface. He created the first true Arabic script type in the Middle East. The first book off the press was in 1734; this press continued to be used until 1899.[7][8]

Languages written with the Arabic alphabet

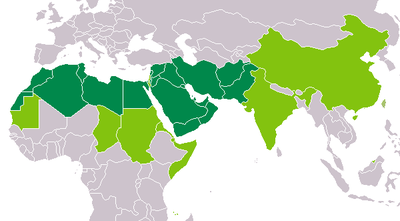

| Worldwide use of the Arabic alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| → | Countries where the Arabic script is the only official orthography | |

| → | Countries where the Arabic script is used officially alongside other orthographies. | |

The Arabic script has been adopted for use in a wide variety of languages besides Arabic, including Persian, Kurdish, Malay, and Urdu, which are not Semitic. Such adaptations may feature altered or new characters to represent phonemes that do not appear in Arabic phonology. For example, the Arabic language lacks a voiceless bilabial plosive (the [p] sound), so many languages add their own letter to represent [p] in the script, though the specific letter used varies from language to language. These modifications tend to fall into groups: all the Indian and Turkic languages written in Arabic script tend to use the Persian modified letters, whereas Indonesian languages tend to imitate those of Jawi. The modified version of the Arabic script originally devised for use with Persian is known as the Perso-Arabic script by scholars.

In the case of Kurdish, vowels are mandatory, making the script an abugida rather than an abjad as it is for most languages. Kashmiri and Uyghur, also, write all vowels.

Use of the Arabic script in West African languages, especially in the Sahel, developed with the penetration of Islam. To a certain degree the style and usage tends to follow those of the Maghreb (for instance the position of the dots in the letters fāʼ and qāf). Additional diacritics have come into use to facilitate writing of sounds not represented in the Arabic language. The term Ajami, which comes from the Arabic root for "foreign", has been applied to Arabic-based orthographies of African languages.

Languages currently written with the Arabic alphabet

Today Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, India, Israel and China are the main non-Arab states using the Arabic alphabet to write one or more official national languages, including Dari, Punjabi, Pashto, Urdu, Kashmiri, Sindhi, and Uyghur.

The Arabic alphabet is currently used for the following:

Middle East and Central Asia

- Kurdish in Northern Iraq, Northeast Syria, and Northeast Iran. (In Turkey, the Latin alphabet is used for Kurdish);

- Official languages Dari (which differs to a degree from Persian) and Pashto and all regional languages including Uzbek in Afghanistan;

- Tajik also differs only to a minor degree from Persian, and while in Tajikistan the usual Tajik alphabet is an extended Cyrillic alphabet, there is also some use of Arabic-alphabet Persian books from Iran; in the southwestern region of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China Arabic script is the official one (like for Uyghur in the rest of Xinjiang);

- Garshuni (or Karshuni) originated in the seventh century AD, when Arabic was becoming the dominant spoken language in the Fertile Crescent, but Arabic script was not yet fully developed and widely read. There is evidence that writing Arabic in Garshuni influenced the style of modern Arabic script. After this initial period, Garshuni writing has continued to the present day among some Syriac Christian communities in the Arabic-speaking regions of the Levant and Mesopotamia.

- Uyghur changed to Roman script in 1969 and back to a simplified, fully voweled, Arabic script in 1983;

- Kazakh in Pakistan, Iran, China, and Afghanistan; and

- Kyrgyz by its 150,000 speakers in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwestern China.

East Asia

- The Chinese language is written by some Hui in the Arabic-derived Xiao'erjing alphabet.

South Asia

- Official language Urdu and regional languages including Punjabi (where the script is known as Shahmukhi), Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Balochi in Pakistan;

- Urdu, Sindhi and Kashmiri in India. Urdu is one of several official languages in the states of Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh; see List of national languages of India. Kashmiri also uses Sharada script;

- The Arwi language (a mixture of Arabic and Tamil) uses the Arabic script together with the addition of 13 letters. It is mainly used in Sri Lanka and the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu for religious purposes.

- Malayalam language represented by Arabic script variant is known as Arabi Malayalam.The script has particular alphabets to represent the peculiar sounds of Malayalam. This script is mainly used in Madrassas of South Indian state of Kerala and Lakshadweep to teach Malayalam.

- The Thaana script used to write the Dhivehi language in the Maldives has vowels derived from the vowel diacritics of the Arabic script. Some of the consonants are borrowed from Arabic numerals.

Southeast Asia

- Malay in the Arabic script known as Jawi is co-official in Brunei, and used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, Southern Thailand, Singapore, and predominantly Muslim areas of the Philippines. Therefore, Arabic script or Jawi can be seen or used for the sign board or market or shop board. Particularly in Brunei, Jawi is practically used in terms of writing or reading for Islamic Religious Educational Program which is like Primary school, Secondary School, College even higher educational institute such as University. In addition, some television programs is associated with Jawi for announcement, advertisement, news, social programs, obviously religious program and etc.

Southeast Asia

- Early history of Islamic belief and culture is experienced by Brunei from the influenced of Arabian merchants. Through the Arabian reached Brunei, some culture of Brunei is mixed with Arab even today some language is derived from Arab words. According to history, during the 14th century the founder of Brunei Sultanate is Sultan Muhammad Shah (1363 to 1402, formerly Awang Alak Betatar) who converted to Islam through the relational marriage with Tumasek (now Singapore) princess (now Johor in which at that time already received the teaches of Islamic faith). However, the influence of Islam is not strong enough at that time in Brunei.

- During 15th century one of Arab merchant named Sharif Ali, who believed was the direct-descendant of Muhammad, his grandchild, was Saidina Hassan r.a who married Sultan Ahmad's daughter, Puteri Ratna Kesuma. He became the third sultan of Brunei and called as Sultan Sharif Ali (also known as Barkat Ali ibnu Sharif Ajlan ibni Sharif Rumaithah). He was made Sultan after Sultan Ahmad died without leaving any male descendants, and as such, at the request of the people of Brunei themselves, he became eligible for the throne after marrying Sultan Ahmad's daughter, Puteri Ratna Kesuma. His legacy by adding "Darussalam" which mean abode of peace after Brunei. Today, in the Brunei flag there is Jawi scripted in the emblem.[9]

Africa

- Bedawi or Beja, mainly in northeastern Sudan;

- Comorian (Comorian) in the Comoros, currently side by side with the Latin alphabet (neither is official);

- Hausa, for many purposes, especially religious (known as Ajami), also includes newspapers, mass mobilization posters and public information;

- Mandinka, widely but unofficially (known as Ajami), (another non-Latin alphabet used is N'Ko);

- Fula, especially the Pular of Guinea (known as Ajami);

- Wolof (at zaouia schools), known as Wolofal.

- Berber languages have often been written in an adaptation of the Arabic alphabet. The use of the Arabic alphabet, as well as the competing Latin and Tifinagh scripts, has political connotations.

Languages formerly written with the Arabic alphabet

Speakers of languages that were previously unwritten used Arabic script as a basis to design writing systems for their mother languages. This choice could be influenced by Arabic being their second language, the language of scripture of their faith, or the only written language they came in contact with. Additionally, since most education was once religious, choice of script was determined by the writer's religion; which meant that Muslims would use Arabic script to write whatever language they spoke. This led to Arabic script being the most widely used script during the Middle Ages.

In the 20th century, the Arabic script was generally replaced by the Latin alphabet in the Balkans, parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia, while in the Soviet Union, after a brief period of Latinisation,[10] use of the Cyrillic alphabet was mandated. Turkey changed to the Latin alphabet in 1928 as part of an internal Westernizing revolution. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of the Turkic languages of the ex-USSR attempted to follow Turkey's lead and convert to a Turkish-style Latin alphabet. However, renewed use of the Arabic alphabet has occurred to a limited extent in Tajikistan, whose language's close resemblance to Persian allows direct use of publications from Iran.[11]

Most languages of the Iranian languages family continue to use Arabic script, as well as the Indo-Aryan languages of Pakistan and of Muslim populations in India, but the Bengali language of Bangladesh is written in the Bengali alphabet.

Africa

- Afrikaans (as it was first written among the "Cape Malays", see Arabic Afrikaans);

- Berber in North Africa, particularly Shilha in Morocco (still being considered, along with Tifinagh and Latin, for Central Atlas Tamazight);

- Harari, by the Harari people of the Harari Region in Ethiopia. Now uses the Ge'ez and Latin alphabets.

- For the West African languages – Hausa, Fula, Mandinka, Wolof and some more – the Latin alphabet has officially replaced Arabic transcriptions for use in literacy and education;

- Malagasy in Madagascar (script known as Sorabe);

- Nubian;

- Swahili (has used the Latin alphabet since the 19th century);

- Somali (see Wadaad's writing) has used only the Latin alphabet since 1972;

- Songhay in West Africa, particularly in Timbuktu;

- Yoruba in West Africa (this was probably limited, but still notable)

Europe

- Albanian;

- Azeri in Azerbaijan (now written in the Latin alphabet and Cyrillic alphabet scripts in Azerbaijan);

- Bosnian (only for literary purposes; currently written in the Latin alphabet; see Arebica);

- French by the Arabs and Berbers in Algeria and other parts of North Africa during the French colonial period.

- Polish (among ethnic Tatars);

- Greek in certain areas and Greece and Anatolia

- Belarusian (among ethnic Tatars; see Belarusian Arabic alphabet);

- Mozarabic, Aragonese, Portuguese, and Spanish, when the Muslims ruled the Iberian peninsula (see Aljamiado);

- Romanian in certain areas of Transylvania (until the 17th century a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire).

Central Asia and Russian Federation

- Bashkir (officially for some years from the October Revolution of 1917 until 1928, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script);

- Chaghatai across Central Asia;

- Chechen (sporadically from the adoption of Islam; officially from 1917 until 1928);[12]

- Kazakh in Kazakhstan (until 1930s, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script);

- Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan (until 1930s, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script);

- Tatar before 1928 (changed to Latin Janalif), reformed in 1880s (iske imlâ), 1918 (yaña imlâ — with the omission of some letters);

- Chinese and Dungan, among the Hui people (script known as Xiao'erjing);

- Turkmen in Turkmenistan (changed to Latin in 1929, then to the Cyrillic script, then back to Latin in 1991);

- Uzbek in Uzbekistan (changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script);

- All the Muslim peoples of the USSR between 1918-1928 (many also earlier), including Bashkir, Chechen, Kazakh, Tajik etc. After 1928 their script became Latin, then later Cyrillic.

Southeast Asia

- Malay in Malaysia and Indonesia

- Minangkabau in Indonesia

- Banjar in Indonesia

- Javanese and Sundanese in Indonesia, used only in Islamic schools and institutions

- Maguindanaon in the Philippines

- Tausug in the Philippines

Middle East

- Turkish in the Ottoman Empire was written in Arabic script until Mustafa Kemal Atatürk declared the change to Roman script in 1928. This form of Turkish is now known as Ottoman Turkish and is held by many to be a different language, due to its much higher percentage of Persian and Arabic loanwords (Ottoman Turkish alphabet);

- Kurdish (Kurmanji dialect) in Turkey and Syria was written in Arabic script until 1932, when a modified Kurdish Latin alphabet was introduced by Jaladat Ali Badirkhan in Syria.

Computers and the Arabic alphabet

The Arabic alphabet can be encoded using several character sets, including ISO-8859-6, Windows-1256 and Unicode, in the latter thanks to the "Arabic segment", entries U+0600 to U+06FF. However, neither of these sets indicate the form each character should take in context. It is left to the rendering engine to select the proper glyph to display for each character.

Unicode

As of Unicode 5.0, the following ranges encode Arabic characters:

- Arabic (0600–06FF)

- (0750–077F)

- (FB50–FDFF)

- (FE70–FEFF)

The basic Arabic range encodes the standard letters and diacritics, but does not encode contextual forms (U+0621–U+0652 being directly based on ISO 8859-6); and also includes the most common diacritics and Arabic-Indic digits. U+06D6 to U+06ED encode Qur'anic annotation signs such as "end of ayah" ۖ and "start of rub el hizb" ۞. The Arabic Supplement range encodes letter variants mostly used for writing African (non-Arabic) languages. The Arabic Presentation Forms-A range encodes contextual forms and ligatures of letter variants needed for Persian, Urdu, Sindhi and Central Asian languages. The Arabic Presentation Forms-B range encodes spacing forms of Arabic diacritics, and more contextual letter forms.

| Arabic[1] Unicode.org chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+060x | | | | | ؆ | ؇ | ؈ | ؉ | ؊ | ؋ | ، | ؍ | ؎ | ؏ | ||

| U+061x | ؐ | ؑ | ؒ | ؓ | ؔ | ؕ | ؖ | ؗ | ؘ | ؙ | ؚ | ؛ | ؞ | ؟ | ||

| U+062x | ؠ | ء | آ | أ | ؤ | إ | ئ | ا | ب | ة | ت | ث | ج | ح | خ | د |

| U+063x | ذ | ر | ز | س | ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ػ | ؼ | ؽ | ؾ | ؿ |

| U+064x | ـ | ف | ق | ك | ل | م | ن | ه | و | ى | ي | ً | ٌ | ٍ | َ | ُ |

| U+065x | ِ | ّ | ْ | ٓ | ٔ | ٕ | ٖ | ٗ | ٘ | ٙ | ٚ | ٛ | ٜ | ٝ | ٞ | ٟ |

| U+066x | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | ٪ | ٫ | ٬ | ٭ | ٮ | ٯ |

| U+067x | ٰ | ٱ | ٲ | ٳ | ٴ | ٵ | ٶ | ٷ | ٸ | ٹ | ٺ | ٻ | ټ | ٽ | پ | ٿ |

| U+068x | ڀ | ځ | ڂ | ڃ | ڄ | څ | چ | ڇ | ڈ | ډ | ڊ | ڋ | ڌ | ڍ | ڎ | ڏ |

| U+069x | ڐ | ڑ | ڒ | ړ | ڔ | ڕ | ږ | ڗ | ژ | ڙ | ښ | ڛ | ڜ | ڝ | ڞ | ڟ |

| U+06Ax | ڠ | ڡ | ڢ | ڣ | ڤ | ڥ | ڦ | ڧ | ڨ | ک | ڪ | ګ | ڬ | ڭ | ڮ | گ |

| U+06Bx | ڰ | ڱ | ڲ | ڳ | ڴ | ڵ | ڶ | ڷ | ڸ | ڹ | ں | ڻ | ڼ | ڽ | ھ | ڿ |

| U+06Cx | ۀ | ہ | ۂ | ۃ | ۄ | ۅ | ۆ | ۇ | ۈ | ۉ | ۊ | ۋ | ی | ۍ | ێ | ۏ |

| U+06Dx | ې | ۑ | ے | ۓ | ۔ | ە | ۖ | ۗ | ۘ | ۙ | ۚ | ۛ | ۜ | | ۞ | ۟ |

| U+06Ex | ۠ | ۡ | ۢ | ۣ | ۤ | ۥ | ۦ | ۧ | ۨ | ۩ | ۪ | ۫ | ۬ | ۭ | ۮ | ۯ |

| U+06Fx | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | ۺ | ۻ | ۼ | ۽ | ۾ | ۿ |

Notes

|

||||||||||||||||

See also the notes of the section on modified letters.

Keyboards

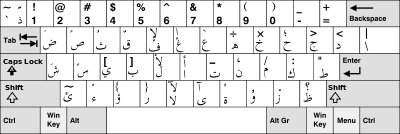

Keyboards designed for different nations have different layouts so that proficiency in one style of keyboard such as Iraq's does not transfer to proficiency in another keyboard such as Saudi Arabia's. Differences can include the location of non-alphabetic characters such as '

All Arabic keyboards allow typing Roman characters, e.g., for the URL in a web browser. Thus, each Arabic keyboard has both Arabic and Roman characters marked on the keys. Usually the Roman characters of an Arabic keyboard conform to the QWERTY layout, but in North Africa, where French is the most common language typed using the Roman characters, the Arabic keyboards are AZERTY.

When one wants to encode a particular written form of a character, there are extra code points provided in Unicode which can be used to express the exact written form desired. The range Arabic presentation forms A (U+FB50 to U+FDFF) contain ligatures while the range Arabic presentation forms B (U+FE70 to U+FEFF) contains the positional variants. These effects are better achieved in Unicode by using the zero width joiner and non-joiner, as these presentation forms are deprecated in Unicode, and should generally only be used within the internals of text-rendering software, when using Unicode as an intermediate form for conversion between character encodings, or for backwards compatibility with implementations that rely on the hard-coding of glyph forms.

Finally, the Unicode encoding of Arabic is in logical order, that is, the characters are entered, and stored in computer memory, in the order that they are written and pronounced without worrying about the direction in which they will be displayed on paper or on the screen. Again, it is left to the rendering engine to present the characters in the correct direction, using Unicode's bi-directional text features. In this regard, if the Arabic words on this page are written left to right, it is an indication that the Unicode rendering engine used to display them is out-of-date.[13][14]

There are competing online tools, e.g. Yamli editor, allowing to enter Arabic letters without having Arabic support installed on a PC and without the knowledge of the layout of the Arabic keyboard.[15]

Handwriting recognition

The first software program of its kind in the world that identifies Arabic handwriting in real time has been developed by researchers at Ben-Gurion University.

The prototype enables the user to write Arabic words by hand on an electronic screen, which then analyzes the text and translates it into printed Arabic letters in a thousandth of a second. The error rate is less than three percent, according to Dr. Jihad El-Sana, from BGU's department of computer sciences, who developed the system along with master's degree student Fadi Biadsy.[16]

See also

- Arabic calligraphy

- Arabic diacritics (pointed vowels and consonants)

- Arabic numerals

- Arabic Unicode

- Arabic Chat Alphabet

- ArabTeX - provides Arabic support for TeX and LaTeX

- Rasm (unpointed consonants)

- Romanization of Arabic

- South Arabian alphabet

- Additional Arabic Letters

- Category: Arabic-derived alphabets

References

- ↑ "Arabic Alphabet". Encyclopaedia Britannica online. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9008156/Arabic-alphabet. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Rogers, Henry (2005). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Blackwell Publishing. p. 135.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Arabic Dialect Tutorial

- ↑ File:Basmala kufi.svg - Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 File:Kufi.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ File:Qur'an folio 11th century kufic.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Arabic and the Art of Printing — A Special Section, by Paul Lunde

- ↑ A Bequest Unearthed, Phoenicia, Encyclopedia Phoeniciana

- ↑ File:Flag of Brunei.svg

- ↑ Alphabet Transitions — The Latin Script: A New Chronology — Symbol of a New Azerbaijan, by Tamam Bayatly

- ↑ Tajik Language: Farsi or Not Farsi? by Sukhail Siddikzoda, reporter, Tajikistan.

- ↑ Chechen Writing

- ↑ For more information about encoding Arabic, consult the Unicode manual available at The Unicode website

- ↑ See also MULTILINGUAL COMPUTING WITH ARABIC AND ARABIC TRANSLITERATION Arabicizing Windows Applications to Read and Write Arabic & Solutions for the Transliteration Quagmire Faced by Arabic-Script Languages and A PowerPoint Tutorial (with screen shots and an English voice-over) on how to add Arabic to the Windows Operating System.

- ↑ Yamli in the News

- ↑ Israel 21c

External links

- Arabic at the Open Directory Project

This article contains major sections of text from the very detailed article Arabic alphabet from the French Wikipedia, which has been partially translated into English. Further translation of that page, and its incorporation into the text here, are welcomed.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||